Warren Buffett Q&A Transcript || 2022 Charlie Rose Interview

"You always want to be around people who are better than you are. They pull you in the right direction."

In early 2022, Warren Buffett spoke to Charlie Rose for over an hour about his investing career and outlook on life.

Over the past few weeks, I transcribed (and lightly annotated) his remarks for posterity and future study.

A few notes:

My main focus is accuracy and readability.

Each transcript is done by hand — without any AI or transcription software assistance — so any mistakes are entirely my own.

I summarized a few of the questions to save space. All of Warren’s answers are transcribed verbatim.

I added footnotes — 33 in all — to provide additional information at relevant points. Hopefully, these will prove useful to readers.

The full transcript is available to all paid supporters. Free subscribers have access to the first 2,000-ish words. (That’s longer than the typical Kingswell article.)

I’ve tried to do my best to ensure that no one feels short-changed.

So, without further ado, here is the complete transcript of Warren Buffett’s latest interview with Charlie Rose…

Charlie Rose: It’s great to see you.

Warren Buffett: Charlie, it’s great to see you, too. I’ve been in Omaha and I think I’ve made, prior to the last week, I’ve probably made two plane flights in two years. Once to see my sister and…

Free at last! (Laughs)

CR: You’re 91.

WB: I’m 91.

CR: Good health?

WB: I couldn’t be in better health. It’s a little bit discouraging to me that my partner in business, life, and everything else — Charlie Munger — is 98. (Laughs)

CR: And still going strong.

WB: I’m still the kid! (Laughs)

CR: You have a successor in place.

WB: We have a successor in place1, but he’s not warming up. (Laughs)

CR: You’re not ready to go.

WB: I’m still in overtime — but I’m out there. (Laughs)

CR: Do you still tap dance to work?

WB: I tap dance to work, Charlie. I’ve always been happy at work, but I’ve never been happier. I’ve got the most interesting — to me — job in the world. I’ve got people you wouldn’t believe that support me. It takes about four or five. It takes a village, to a degree. But I’ve got three people sitting right down the [hall], within twenty or thirty feet of me: my assistant, Deb Bosanek; the fellow that handles all the trades I tell him to do in the morning and money and billions flow in and out and he takes care of it all, Mark Millard; and I’ve got the chief financial officer, Marc Hamburg, who knows more than most of the finance offices and legal offices and everything else in the world. We’ve all worked together for dozens of years and we like each other and everybody helps me. It couldn’t be better.

CR: Choosing who you work with —

WB: It’s everything. I write a little bit about it in the annual report, but choosing what you do and who you do it with [is crucial]. If you’re like me, you’re gonna spend 70 years or something [doing it].

My assistant hasn’t worked the whole time with me, but she went to work for Berkshire when she was seventeen. She still looks seventeen. And, now, she’ll be with us fifty years at Berkshire.

They know me forward and backwards. They accept my eccentricities. They help me.

I would say this: if you take Mark Millard2, I walk in in the morning (or I call him first) and I tell him exactly — I’ve already done it for today — I tell him exactly what we want to do and he does it all day. Some days, a good many days, he moves billions of dollars — purchases and sales. He takes care of the whole thing.

CR: When do you make those decisions?

WB: I think all the time. I’m on the clock at Berkshire all the time.

CR: Walk me through a typical day.

WB: Well, a typical day… I get up, usually, at a few minutes before seven so I can catch the seven o’clock news and the network news in Omaha — so I get up a few minutes before that. Sometimes I turn on the network news — I always turn on CNBC — and I look at what prices are doing and what’s happened in Europe and what’s happened in Japan.

The market opens, our time, at 8:30 — although we’re doing maybe things in Japan or Germany, too. I call Mark [Millard] at 8:00 — with the market opening at 8:30 — and I tell him exactly what to do for the day. And I probably won’t change it during the day. It’s usually a percentage of something. I will say, “Buy or sell x% of the trading volume,” and I’ll give him a list of things. If there’s a limit of price, I give him the price. And then he does it all day. I don’t need to check with him. He sometimes does billions of dollars worth of business.

He buys the Treasury bills which we… In the last couple of years, we probably bought $5 billion every Monday. I would guess that we might be the biggest buyer. Just week after week after week after week.

CR: You made your first investment when you were eleven years old?

WB: In 1942, eighty years ago, I took $114.75 — every penny I had saved — and I bought three shares of Cities Service preferred [stock]. And Cities Service3 was a pretty well known name [back] then. In fact, in 1920, Cities Service — I think — was the fourth-largest company in the United States in terms of number of shareholders. It was a big company.

It had a preferred stock that was selling at $38 that had started skipping the dividends during the Depression, so it accumulated dividends on it of $60 or $70. And, of course, it was par value of $100, too — and it was selling at $38.

At breakfast one morning — I followed all the stocks every day — but then I made my plunge. I had roughly this amount of money, so I bought three shares. I don’t remember this precisely, but I think I told my dad in the morning, “Now! Let’s move, Dad.” Pop, I called him. I said, “Let’s move, Pop!”

CR: You felt the thrill of it then.

WB: Oh, I had been reading about it and following it — the whole market. I really had read every book in the Omaha Public Library that was on the stock market.

CR: By eleven?

WB: By eleven, I’ll guarantee you. And some of them twice. I started out reading the ones in my dad’s office. I just loved to read. I read other things, too.

I knew more when I was eleven than I know now. (Laughs) In terms of the actual mechanics of the stock market, I don’t know what happens when I put an order in now. The machinery of the way orders are executed now… I would know if I sat and worked in a trade room for a day or two, but I don’t really know the mechanics of what happens when an order is processed today as [well as] I did when I was eleven.

CR: What is it that you enjoy the most about it? You don’t pick stocks — you pick companies.

WB: Yeah, that’s exactly [right].

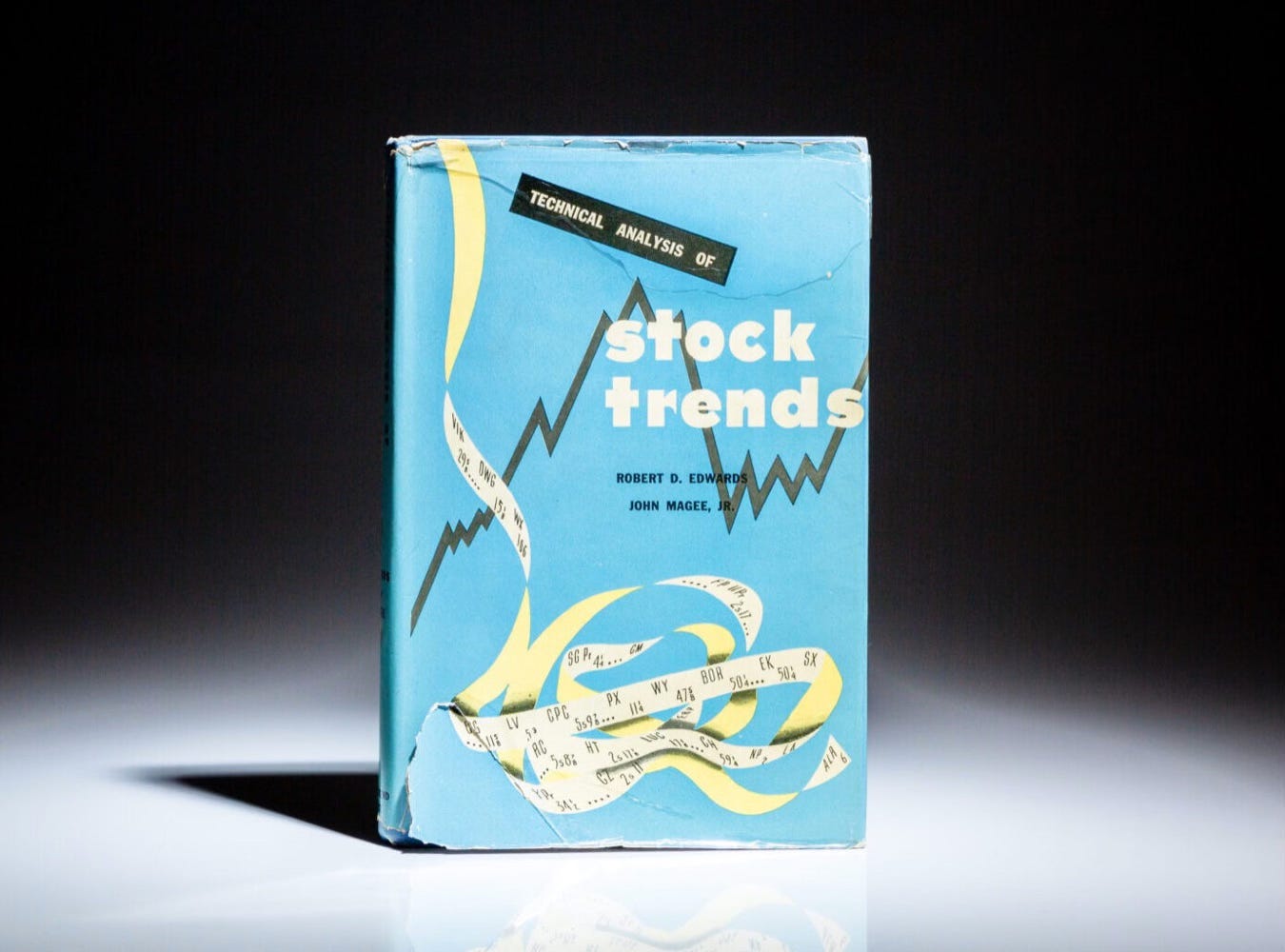

But, when I was eleven, I picked stocks. I had the whole wrong idea. I was interested in watching stocks and I thought stocks were things that went up and down. I charted them. I read books on technical analysis. I read Edwards and Magee4 — I think that was the classic then. Hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of pages and I read that whole thing over and over again. I read everything.

[For] the first eight years, I thought that the important thing was to predict what a stock would do and predict the stock market. Then I read Ben Graham, I was nineteen or twenty, and I realized that I was doing it exactly the wrong way. But it didn’t hurt that I had that background [of technical analysis] or anything.

I rejiggered my mind when I read the book, The Intelligent Investor. And, from that point, I never bought another stock — I bought businesses that happened to be publicly traded. I became an owner of a business and I did not care whether a stock went up or down the next day or the next week or the next month or the next year. I didn’t have any idea what it would do. I didn’t know what the stock market would do. But I knew businesses. I knew some businesses.

CR: I’ve asked people about your genius —

WB: No, I’m a bright guy who’s terribly interested in what he does, so I’ve spent a lifetime doing it and I’ve surrounded myself with people that bring out the best in me. You don’t need to be a genius in what I do. That’s the good thing about it.

If I would have done physics or a whole lot of other subjects, I’d be an also-ran. But I am in a game that you don’t need… You probably need 120 points of IQ. But 170 doesn’t do any better than 120. It would probably do worse. You don’t really need brains.

CR: What do you need?

WB: You need the right orientation. 90% of the people — I’m pulling that figure out of the air — but 90% of the people that buy stocks don’t think of them the right way. They think of them as something that they hope goes up next week. And they think about the market as something they hope goes up. If it’s down, they feel worse. I feel better [when the market goes down].

CR: What do you think about?

WB: I think about what the company is going to be worth ten or twenty years from now. And I hope it goes down when I buy it because [then] I’ll buy more.

CR: You have a competitive spirit, clearly.

WB: Yeah. Well, you’ve got to be careful about what you compete in. It’s a good thing that I don’t have a competitive spirit in chess or football or anything like that. (Laughs) No, I’m an observer there. I enjoy watching things like that, but I try to keep my competitive spirit in a game where I can win.

CR: Do you have a killer instinct?

WB: Nah, not exactly. I wouldn’t call it a killer instinct, but I do know this — when I want to do something, I always want to do it big.

I put my whole net worth in Cities Service preferred.

CR: $120.

WB: $114.75. (Laughs)

I put my whole net worth in and, since that day (March 11, 1942), I have never had less than 80% of my money in American business. You can call them stocks, but I see them as American business. I’ve owned a piece of American business — at least 80% — at all times. I don’t want to own anything else.

I want to own a home and some things that my family wants and all that, but owning five homes doesn’t mean anything to me because I’m happy in one home. There’s a certain amount of things that [will] go wrong with everything. If I’ve got two homes, I know I’ve got more problems — and I don’t have more happiness.

CR: What brings you happiness?