Warren Buffett's 1969 Annual Letter — Yes, It Actually Exists

"You have let me play the [money] game without telling me what club to use, how to grip it, or how much better the other players are doing."

Happy Tuesday and welcome to our new subscribers!

Special thanks, too, to those who recently became paid supporters! ❤️

I thought about naming this article “The Lost Warren Buffett Letter” — but that seemed a tad hyperbolic. (Alas, I’m not very good at playing the clickbait game…)

Can a letter really be called “lost” when it’s been sitting right under our noses — in an official Berkshire Hathaway publication, no less — for close to a decade?

Probably not.

Nevertheless, Buffett’s final annual partnership letter — dated February 18, 1970 — hasn’t gotten nearly the attention it deserves. In fact, it’s still missing from virtually every collection of Buffett letters out there on the internet.

But, thankfully, this letter does exist — and is reprinted in its entirety on pages 37-39 of Berkshire’s 50th anniversary book, Celebrating 50 Years of a Profitable Partnership.

For those (normal) people who don’t track Berkshire Hathaway’s history in obsessive detail, here’s a quick background:

On May 29, 1969, Warren Buffett announced to his partners that he would be winding up Buffett Partnership Ltd. and retiring at year’s end.

Over the course of 1969, he wrote to his partners a few more times with all of the details of BPL’s liquidation process — including the proportional dispersal of shares in Berkshire Hathaway and Diversified Retailing. He also sought to find his erstwhile partners a safe place to land with their money.

Ordinarily, Buffett wrote an annual letter to his partners each January to review his investment performance over the previous year. Except, in every collection of these letters that I’ve ever seen, there is no annual letter for 1969.

This didn’t seem overly unusual to me. I assumed that Buffett was too busy with the liquidation process of BPL to bother writing one last annual letter.

And, since he didn’t sign his name to the Berkshire letter until 1970, I resigned myself to the fact that he wrote no annual letter for 1969.

Happily, I was wrong about that.

As it turns out, Warren Buffett did write an annual letter to his partners for 1969. I don’t know why it has disappeared from all modern collections, but it definitely exists.

(Note: I’m certainly not claiming to be the first one to discover this. I just want to bring this letter’s message to a wider audience — especially since there’s so little mention of it online.)

I’m not going to reprint the entire letter here — I don’t want to step on any toes over at Berkshire Hathaway since the 50th anniversary book is still on sale — but I’ve pulled out the parts that should be of most interest to readers…

BPL’s 1969 Performance

Our Partnership life ended on a symmetrical note. I consider 1957 and 1969, our beginning and terminal years, to have been the two most difficult twelve-month calendar periods that we faced during our operating history. It was fortunate that our Partnership symmetry went no further than this — an ending capital equal to our beginning capital, despite a classical aesthetic balance, might not have produced total fulfillment.

Warren Buffett didn’t have to worry about that last point. BPL ended up with way more capital than it started. It was almost as if each and every partner had won the lottery under Buffett’s extraordinary money management.

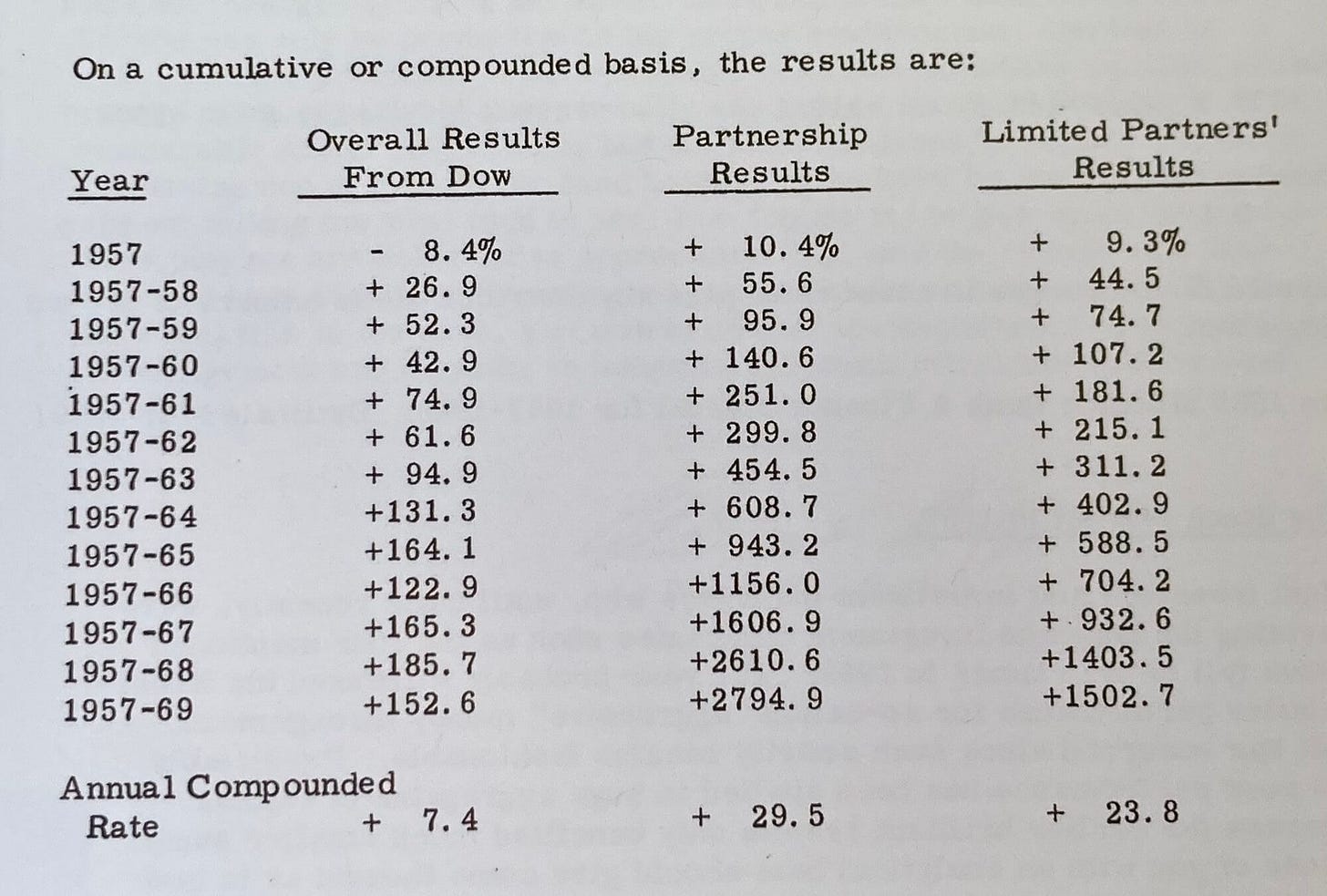

Over its thirteen-year lifespan, BPL racked up an incredible 2,794.9% cumulative gain (as compared to the Dow at 152.6%). Even after Buffett collected his share of the proceeds, limited partners finished with a life-changing 1,502.7% return.

But Buffett was right about 1969 being a relatively challenging year. BPL’s 6.8% annual gain was the smallest of the partnership era.

Nevertheless, it still crushed the Dow (his preferred benchmark at the time) by 18.4% that year. As usual, Buffett thrived when the wider market struggled.

“Chain Letter” Money Management

[1969] probably witnessed the worst relative performance for so-called “aggressive” money management that has occurred since such activity became fashionable. Predictably, the poor performance has been applied to huge aggregates of capital whereas the earlier brilliant results only benefited much smaller sums.

Those of you with an analytical bent should give some thought as to how accurately the standard mutual fund literature portrays the investment record of a fund which has a 100% gain in one year on $1 million of assets, and a 25% loss in a subsequent year on $1 billion (attracted by the earlier performance) of assets.

The “chain letter” phenomenon, whether created intentionally by a financial Machiavelli or accidentally by a public responding to its baser emotions, tends to produce an identical effect — a few people, the ones who intentionally or accidentally mail the first letters, make a great deal of money; and a vastly greater number on the outer ring of concentric circles lose money while behaving in a manner they think is certain to succeed because of the obviously bountiful results to early participants.

Many of the better investment management records in the 1964-68 period were at least partial beneficiaries of corporate chain letter activity and, to the extent they over-stayed their hand in 1969, a substantial bath was taken.

Warren Buffett’s disillusionment with the state of the investing world in the late 1960s and early 1970s was one of the big reasons that he closed his partnership.

That, and he was struggling to find value in this “aggressive money” era.

Closing Time

Warren Buffett also provided an update on BPL’s liquidation process. He told partners that approximately $99 million of partnership assets — in the form of cash and shares of Berkshire Hathaway and Diversified Retailing — had already been distributed.

But, even so, the job wasn’t quite done.

We are down to about $6 million of net assets, largely represented by our holdings of Blue Chip Stamps. However, we have miscellaneous other items, including such little gems as about 90% of a fractional interest in the royalty under a gas well in Bee County, Texas (producing less than $4,000 per year) and 80% of a small store building in South Chicago.

It is much easier to get into business than to get out of it. My expectation is that we will get everything finally wound up during 1971, but this is very tentative — in any event, I think it unlikely we make a further distribution in 1970. The office will be maintained at Kiewit Plaza (although perhaps on a different floor) through 1971 when our lease expires.

As it turns out, Kiewit Plaza would not be rid of Buffett and co. so easily.

“And My Thanks”

This would not be Warren Buffett’s last letter to his partners. After all, just one week later, he sent out a lengthy “elementary general education on bonds” to anyone interested in moving their partnership money into fixed-income securities.

But this 1969 annual letter afforded him a chance to say goodbye — and thank you — to the men and women who had trusted him with their money for so many years.

Everyone walked away happy — and rich — but this was still a bittersweet moment for Buffett and his partners. The final chapter in a very profitable story.

Normally, the liquidation of an enterprise implies institutional or personnel weaknesses. Our own case represents the opposite extreme. I consider the BPL staff to be superior to that of any organization I have seen. Gladys [Kaiser], Donna, John [Harding], and Bill [Scott] have done everything asked of them — and, sometimes, it was plenty — in the most accurate, prompt, and pleasant manner possible. They are exceptionally high-grade, talented people.

Don’t get any ideas about hiring them — John is going with Bill Ruane* — I expect Gladys and Bill [Scott] to become employed by Berkshire Hathaway, Inc., primarily in connection with the bond activities of the bank and insurance company — and Donna will keep tab on the run-out of BPL over the next couple of years.

[*When BPL closed, Buffett recommended two money managers to his partners: Bill Ruane and Sandy Gottesman. Ruane created the Sequoia Fund in 1970 to accommodate the flood of former BPL partners who sought his management. As Buffett points out in the 50th anniversary book (published in 2015), a $100,000 investment in Sequoia would have then been worth about $40 million.]

Ben Rosner [Associated Cotton Shops] and Jack Ringwalt [National Indemnity] have done extraordinary work for BPL since acquisition of their companies by DRC and BH. Their efforts over the past three years have contributed to a significant degree to the increased valuations applied to the controlled companies at each year-end. Our figures would have been considerably poorer had they turned in only the normal managerial job.

Without the right group of partners, there would have been no BPL. Efforts can only be productive in the right environment, and that is what you have provided. I have probably been able to utilize my time and energy more effectively than virtually any money manager working with comparable sums. My activity has not been burdened by second-guessing, discussing non sequiturs, or hand-holding. You have let me play the game without telling me what club to use, how to grip it, or how much better the other players are doing.

I’ve appreciated this, and the results you have achieved have significantly reflected your attitudes and behavior. If you don’t feel this is the case, you underestimate the importance of personal encouragement and empathy in maximizing human effort and achievement.

I imagine that Buffett would say much the same thing about Berkshire shareholders today.

I was just browsing through the 50th anniversary book the other day. It’s strange how it’s not more widely read and discussed given that everything in it is implicitly endorsed by Buffett!

Thanks, love the old letters. I still remember typewriters.