No Bad Risks, Only Bad Rates — And Other Lessons From National Indemnity Founder Jack Ringwalt

Jack Ringwalt did not just play the game. He rewrote the rules.

“It was National Indemnity that made it all happen at Berkshire Hathaway,” said Warren Buffett about his first significant acquisition as chairman of the struggling New England textile company.

When Buffett shelled out $8.5 million for the Omaha-based insurer in 1967, he took his first bold step away from the faltering textile trade and into more profitable pastures. Many more acquisitions followed in the ensuing decades, but the particulars of the insurance business — with its float providing a steady flow of cash for investment — made National Indemnity the poster child for Berkshire’s new era.

And none of that would have been possible without founder Jack Ringwalt, the property-casualty maverick who built National Indemnity from the ground up — and then handed the keys over to Berkshire.

Ringwalt’s career, captured in his pithy, no-nonsense autobiography (Tales of National Indemnity Company & Its Founder, Jack Ringwalt), reads like a technicolor novel in the drab, gray world of insurance. A college dropout with a knack for defying the norms, he was something of a square peg in an industry of round holes.

But he made it work anyway.

Ringwalt sparred with regulators, outmaneuvered industry giants, and embraced risks that made others blanch — provided, of course, that the price was right.

Simply put, Jack Ringwalt did not just play the game. He rewrote the rules.

The greatest opportunities often lie where others fear to tread

After a fiery fall-out with his first employer — and briefly swearing off selling insurance forever — Ringwalt was pulled back in after his personal investments soured in the early 1930s. Going it alone, the early returns were modest — just $700 in commissions during the first year — but he assiduously carved out a niche for himself by taking on unusual problems that his competitors waved away.

Ringwalt soon came to an important realization: newcomers can’t afford to blend in. “My competitors had more friends, more education, more determination, and more personality than I,” he wrote, so chasing the same business as all the other guys would leave him penniless.

This home truth led Ringwalt down some wild paths…

Take the case of the widow hoping to collect the estate of her late husband, a missing-and-presumed-dead bootlegger. Armed with a tip from the widow’s attorney — who, in a twist straight out of a noir thriller, had defended the bootlegger’s murderer and knew that the unfortunate man’s body currently sat in cement at the bottom of Puget Sound — Ringwalt secured a bond with a top-tier firm and closed the deal.

National Indemnity itself was born from a discarded opportunity. In Omaha, independent cab companies were unable to get state approval because their current insurers were deemed too risky. Ringwalt was offered the chance to find suitable coverage for them. “I started on the top floor of the Insurance Exchange Building [in Chicago] and asked every office if they would consider the Omaha independent cabs at any price,” he wrote. “It took me three days to get a civil answer.” Eventually, he struck gold with Lloyd’s of London. That inspired Ringwalt to go all in — and, in 1940, he scraped together $125,000 and launched National Indemnity to “write cab business and other hard-to-place business”.

And then there was the local radio station that needed coverage for a $100,000 treasure hunt. Ringwalt not only wrote the policy, but also the hunt’s cryptic clues like “A dandelion is not a rose; you are within a block when you pass by Joe’s”. He even buried the treasure — so well, in fact, that nobody found it. The stunt sparked similar contests in other cities, but only in San Francisco did someone win the grand prize. Ringwalt chalked it up to his jangled nerves in the busy city traffic, which led him to skip his usual precautions against being followed. Still, National Indemnity walked away from these contests with a cool $150,000 plus expenses, paying out just $50,000 to the lucky San Francisco sleuth.

There are no bad risks in insurance — only bad rates

This maxim was Ringwalt’s north star, the iron-clad principle that allowed him to fearlessly pursue unusual and unwanted risks without driving himself right out of business. Almost anything can be intelligently insured, so long as you charge enough for the coverage.

(It’s also reminiscent of one of my favorite Warren Buffett lines. “I can go into an emergency ward and write life insurance,” he said in 1990, “if you let me charge enough of a premium.”)

When evaluating potential opportunities, Ringwalt’s open mind welcomed the weird and the wild — and he wrote many policies on offbeat ventures that others wouldn’t touch with a ten-foot pole. But, when it came to pricing, that flexibility vanished. If the market would not meet his rate, Ringwalt never blinked. He just waved goodbye to the deal with an indifferent shrug.

“When business is unprofitable to the companies in general,” wrote Ringwalt, “our premium volume has taken a very sharp spurt and when business has been profitable for most companies, we have run into very unintelligent competition and have had to cut down temporarily on our writings.”

The insurance merry-go-round is always the same: profitability lures rivals who slash rates to grab market share, only to crater when losses inevitably pile up. And when the industry bleeds, fly-by-night competitors vanish, prices climb back to normal, and the cycle starts spinning anew. “This pattern will keep repeating,” he wrote. “It makes no sense, but it’s human nature.”

Ringwalt steadfastly refused to play that sucker’s game — a tradition that continued under Berkshire’s aegis. From 1986 to 1999, National Indemnity’s revenue nosedived 85% as profitable premiums evaporated. But, rather than succumb to the pressure to write more business at any price, Buffett and co. urged employees to wait patiently for the right pitch (so to speak). Some things never change.

Insurance is not for the faint of heart

Over the years, Ringwalt faced a frustrating parade of deceit and malice. Like when agents embezzled a large portion of National Indemnity’s policyholders surplus. Or the time someone snuck an “infinitesimal Jr. after the guarantor’s name” on a contract in order to trick the insurer into accepting a worthless guarantee. Or the swindler from Texas who made off into the night with $50,000 of National Indemnity’s money after forging an audit report on stolen CPA letterhead.

In one notable showdown with an unnamed state, regulators dredged up an obscure, long-forgotten law decreeing that any company using “National” in its name could face fines or even jail time. A blatant shakedown, but a successful one. Ringwalt coughed up the contested $25,000 to make the problem go away.

Perhaps the most galling case involved a woman who insured her husband’s building for a wildly inflated amount — only for it to go up in flames a day before the policy was to end. Ringwalt’s gut screamed fraud at this textbook case of arson, but evidence was hard to come by. In the end, National Indemnity only wriggled off the hook after the claimant botched the lawsuit just as the statute of limitations slammed shut.

Insurance is a brutal arena. A high-stakes poker game where cheaters, chiselers, and chance are always at the table. When Ringwalt finally decided to sell out to Buffett, who could blame him?

Your reputation is worth its weight in gold

(Someone should write a whole article about this…)

For Ringwalt, trust was the currency that fueled his rise in the insurance world. He guarded it fiercely — and never took it for granted. As a scrappy upstart who slowly clawed his way to respectability in the industry, earning the faith of a global juggernaut like Lloyd’s of London felt like a dream come true.

“I had a marvelous asset in the confidence which Lloyd’s Underwriters had in me,” he wrote. “If I did not abuse that confidence by trying to get rich too quick, there was no telling how profitable that relationship would be.”

“I have tried to use this advice in my dealings with other companies and I also have tried with considerable success to sell this same idea to the general agents of the National Indemnity Company. I believe that this philosophy is the very best advice that I can give to an agent.”

Forging that reputation, though, took a fair bit of grit. Early on, Ringwalt landed the chance to write business for Peter Kiewit Son’s, a prestigious local construction firm, and he was hell-bent on proving himself. “The business was profitable, but sometimes nerve-wracking as he would have one of his men call me on New Year’s Eve and want immediate binders in Greenland or some godforsaken place. I used to spend my holidays telephoning around the world trying to line up reinsurance as I hated to let the firm know or think that I could not handle anything thrown at me within a very few hours.” That hustle cemented Ringwalt as the man who always delivered.

Mutual trust also set the stage for Berkshire’s acquisition of National Indemnity. In January 1967, Buffett called up Ringwalt and wanted to meet. About what, the insurance man did not know. In fact, he initially thought Buffett was trying to find out which marketable securities Ringwalt had been buying.

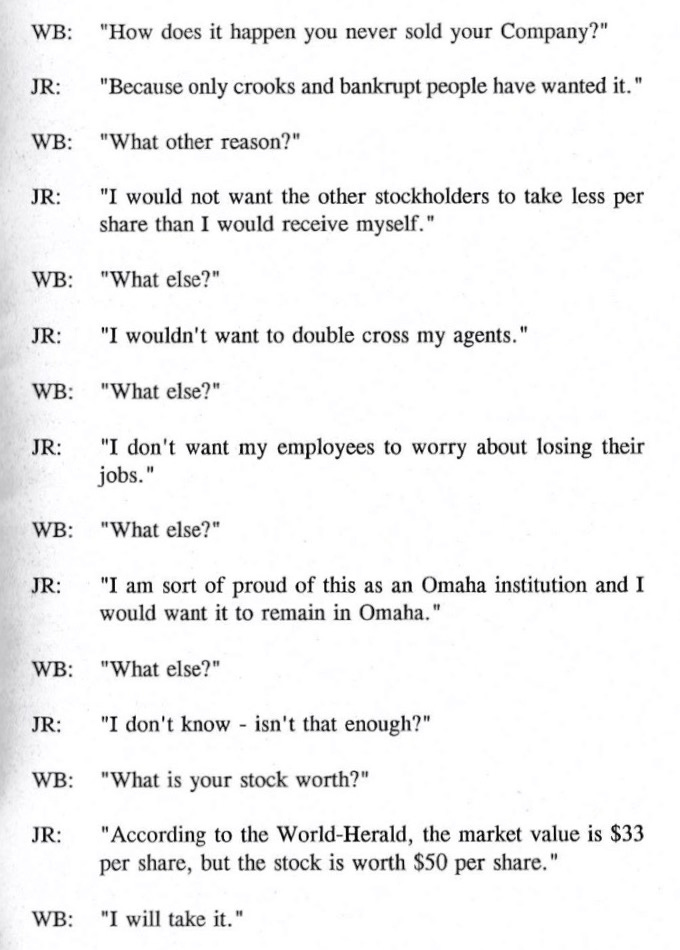

But, instead, the conversation took a very different turn:

In true Buffett fashion, the whole thing took less than fifteen minutes.

Ringwalt was stunned by the on-the-spot offer, but knew that National Indemnity would be in good hands. “I thought that Mr. Buffett at least had an honest reputation and was financially responsible and that it might not be such a bad idea,” he wrote.

After signing on the dotted line, Ringwalt only planned to stay on for a month or two to ease the transition, “but I found Mr. Buffett to be a very considerate chairman of the board and I did remain with the company for more than six years”.

A big part of the natural rapport between the two men came from the enthusiasm they each felt for their respective businesses. Buffett, famously, says that he tap-dances to work each day — and Ringwalt was cut from much the same cloth. “I feel that no man is as fortunate as one who has enjoyed the work which he is doing or has done,” he wrote. “I do not know of anyone who has enjoyed the connection with a company as much as I have my connection with National Indemnity Company.”

Passion and principles lead to extraordinary things.

Amazing and informative. I recall that Charlie, in one of the last interviews of his life, assured the assembled that he self-insured as soon as he was wealthy enough to do it. In "Thinking Fast and Slow," Kahneman notes that insurance is something that poor people buy from rich people. Charlie did insure his vehicles: that is a statutory mandate for obvious reasons. He said he was required to and he did. Note how clearly he distinguished the duty and the fulfillment thereof!

Do you know where I can find Jack’s autobiography? A Google search didn’t bring up much.