I once heard it said that a stock portfolio is a lot like a bar of soap. The more you handle it, the smaller it gets.

Most investors would agree with this. The best results tend to come with the least amount of activity and trading.

But, as anyone who’s dabbled in the money game well knows, that’s easier said than done.

Everything, it seems, conspires against the patient investor.

Market movements, down to the second, are just a click away. Entire cable networks are devoted to talking heads squawking about macroeconomic outlooks, the winners and losers of the day, and often-contradictory stock tips. And, even if you manage to avoid all that, FinTwit 🐦 beckons with thread after thread of advice and judgment.

Taking all of the above into account, can you really blame investors for falling under the spell of short-term thinking and “Do Something!”-itis?

Thankfully, as it turns out, there is a better way…

Sir John Templeton made his name on Wall Street with a series of gutsy bets near the start of World War II. As news of the German blitzkriegs reached our shores, the young investor instructed his broker to buy everything (on borrowed money, no less) that was selling for less than $1 per share.

Including companies in bankruptcy.

A few years later, after the American economic machine kicked into high gear and turned the tide of war against the Axis, Templeton cashed in and quadrupled his original outlay of $10,000.

Wealth only made possible because he refused to succumb to the panicking herds all around him. There aren’t too many better (real-life) examples of the old Warren Buffett axiom to be greedy when others are fearful.

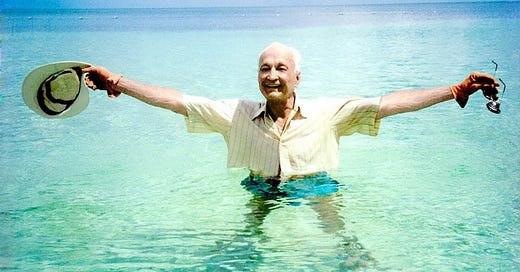

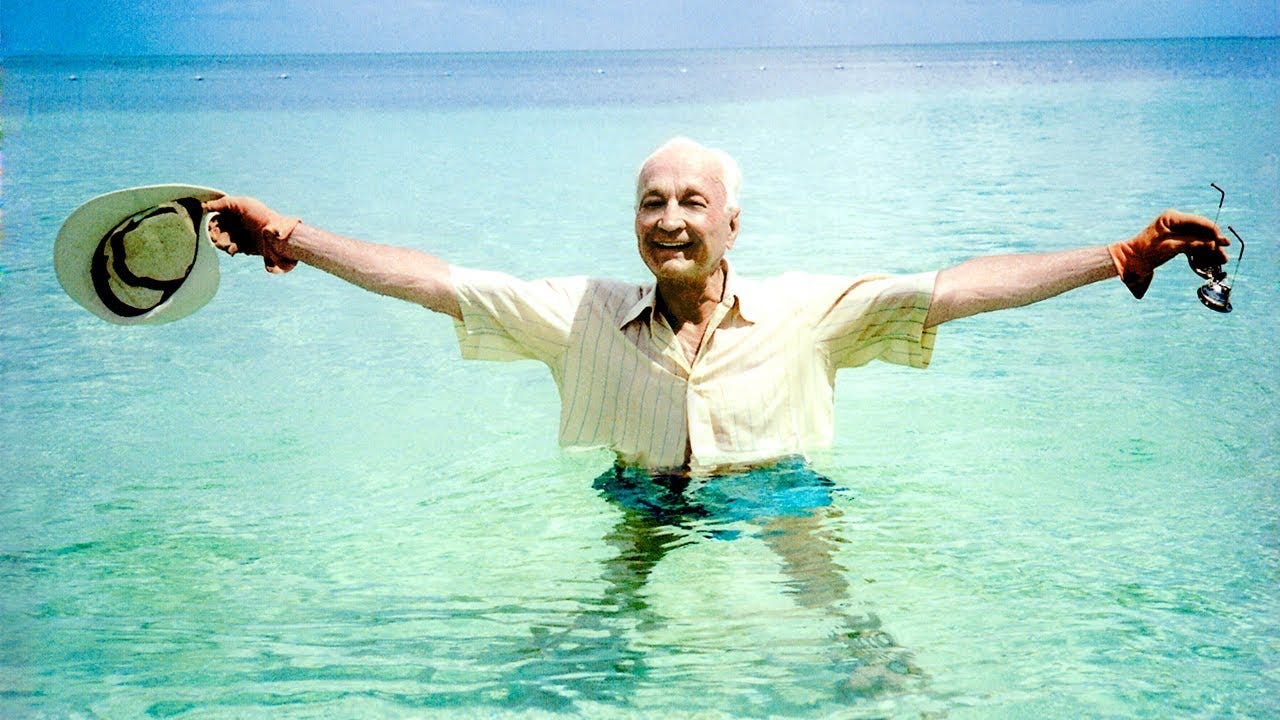

But, for my money, Templeton achieved Wall Street immortality by leaving the manic craziness of New York City behind for the laidback serenity of the Bahamas in 1968.

He built an antebellum-style mansion on a hill overlooking Lyford Cay — but this was no sleepy retirement on a sun-swept Nassau beach.

Far from it!

Templeton was simply escaping the deleterious hustle and bustle of Wall Street.

Such a move might seem vaguely odd today, but in the internet-less world of the 1960s, it was unthinkable. In one fell swoop, Templeton severed himself from the nerve center and beating heart of finance. He unplugged from the market machine.

And, to everyone’s astonishment, it made Sir John Templeton a much better investor.

When Templeton arrived in the Bahamas, he discovered that copies of his beloved Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times typically arrived a day or two late. What would be a fate worse than death for overstimulated rat racers in NYC, though, proved to be balm for the intelligent investor’s soul.

Since his newspapers usually showed up late, Templeton couldn’t be seduced into overreacting to whatever happened to be the breaking news of the day. By the time he read about it, the moment for action had long passed.

Inaction won out by default.

George Goodman, host of “Adam Smith’s Money World” on PBS, once asked Templeton about his decision to abandon New York City and run his mutual funds (worth billions of dollars) from Lyford Cay.

With a smile and a gentlemanly, Southern drawl, he knocked back the question.

Templeton: We did move here because it is so very pleasant, but we now have found that, in the 22 years we’ve lived here, the performance of our mutual fund is better than the 25 years when we managed them from Radio City in New York.

Goodman: How do you account for this? You could work at Radio City and do things differently [from other investors].

Templeton: Yes, we tried to — but we’d go to the same meetings as the other security analysts and the people who speak are so sensible that we can’t help being influenced. It’s much easier to be odd when you’re a thousand miles away.

Goodman, who built his career on mingling with market insiders and then (anonymously) bringing their tales of Wall Street to a wider audience, expressed similar bewilderment at Warren Buffett’s decision to set up shop in Omaha.

In one of Buffett’s first television interviews, the PBS host (and author of many excellent books) asked him about his off-the-beaten-path home.

Buffett laughed and said, “Well, believe it or not, we get mail here and we get periodicals and we get all the facts needed to make decisions. And, unlike Wall Street, you’ll notice we don’t have fifty people coming up and whispering in our ears that we should be doing this or that.”

“We get facts, not stimulation, here,” he finished.

Later, Buffett expounded on the point:

“If I were on Wall Street, I’d probably be a lot poorer. You get overstimulated on Wall Street. You hear lots of things. You may shorten your focus and a short focus is not conducive to long profits. Here, I can just focus on what businesses are worth.

I don’t need to be in Washington to figure out what The Washington Post newspaper is worth. And I don’t need to be in New York to figure out what some other company is worth. It’s an intellectual process and the less static there is in that intellectual process, really, the better off you are.”

And, not at all because I need to pad out the ol’ word count a bit, here’s a similar sentiment from John Train’s “Dance of the Money Bees” (1974):

Enthusiastic hyperactivity is, in fact, the hallmark of the losing investor. The world is not transformed from one day to the next, and the average investor makes less money with his brain than in what in chess is called his Sitzfleisch, or patient rear end.

So, obviously, Sir John Templeton was on to something.

But, for many of us lowly plebes, picking up sticks and moving to the tropics isn’t really an option.

What to do?

Here are five ways to emulate Sir John Templeton’s example and tune out the cacophony of news, emotions, and information overload that plagues so many of us…

(1) Hide the Stocks app

Once upon a time, I installed the Stocks app as a permanent widget on my iPhone and iPad home screens.

Big mistake.

Up-to-the-second stock quotes, right in front of your face whenever you open your phone, is never a good idea. That way lies madness. Hide it, delete it, whatever.

While Templeton missed out on the digital temptations of the smartphone era, he did his best to hold the flood of information at bay. He instructed his brokers to never call him at Lyford Cay. If they thought Sir John needed to see something, they were to send it to him in writing.

The man was never in a hurry.

(2) Learn to love dividends

Dividend-paying stocks, particularly those growing outfits like the Dividend Aristocrats and Kings, free investors from the daily fluctuations of the market.

Building a dividend-focused portfolio also lessens the importance of capital gains. Such investors can ignore price swings altogether — and spend their time monitoring the operating health of the companies in question.

After all, when dividend checks are rolling in on a regular basis, who cares if the S&P 500 went up or down that day?

(3) Listen to Benjamin Graham

One of the most important lessons passed down by the great Benjamin Graham, the father of both security analysis and value investing, is that stocks are not just ticker symbols to be flipped for a quick buck.

Instead, they are small pieces of real businesses — and, for as long as you keep them, you’re entitled to a proportional claim on that company’s earnings and profits.

Internalize that reality and you’ll be well ahead of the game.

No one would buy a house, a farm, or a rental property and then immediately start listening to sales offers — especially lower-priced ones. But that’s exactly what people do when they buy shares in a company and then get itchy hands when the price falls.

Totally irrational… and all too common.

(4) Create a “mad money” account

No, this doesn’t mean to YOLO all your money away on Jim Cramer stock picks.

I’m not trying to bankrupt anyone here.

But, if you’ve got Wall Street fever, consider setting up a “fun and games” brokerage account — funded with a relatively small amount of disposal income — where you can feel free to wheel and deal to your heart’s content.

In theory, this should help satisfy those speculative cravings — without negatively affecting your main accounts.

(5) Find ways to fill your time

Idle hands may or may not be the devil’s workshop, but an idle, unoccupied mind usually turns an investor into his or her own worst enemy.

In other words, sitting around and watching the ups and downs of the market each day won’t lead you anywhere good.

Any activity that engages your mind and soaks up time will fit the bill. Work on a side hustle, take up a new hobby, or even veg out with a video game — it doesn’t matter. Whatever will keep you from obsessing over price drops or the latest analyst report will also protect you from panic selling and hyperactivity.

Sir John Templeton loved to hang out on the beach near his home, either reading or basking in his sunny surroundings. Our options might not be as glamorous, but they serve a similar purpose.

And, oddly enough, it’s often in these quiet moments — away from the money game — that we have our best investing ideas.

Godspeed.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this issue of Kingswell, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends (and enemies) so they don’t miss out. It only costs you a few clicks of the mouse, but means the world to me. Thank you!

Disclosure: This is not financial advice. I am not a financial advisor. Do your own research before making any investment decisions.