The Berkshire Beat: November 22, 2024

All of the latest Warren Buffett and Berkshire Hathaway news!

Happy Friday and welcome to our new subscribers!

Special thanks, too, to those who recently became paid supporters! ❤️

The annotated transcript for November will go out to paid subscribers on Monday. And, with the one-year anniversary of Charlie Munger’s death fast approaching, there was only ever one option for this month: the extended version of his final interview with CNBC’s Becky Quick.

CNBC released a rough transcript of the condensed version of this interview, but I don’t think there has been one for the 100-minute-long extended cut. In a sense, this is Charlie’s parting message to us all.

So, if you’ve been on the fence about upgrading, there’s no time like the present.

Now, with that bit of housekeeping out of the way, let’s turn our attention to the latest news and notes out of Omaha…

Not to dwell on a morbid subject, but many of the men and women who helped to build Berkshire Hathaway into the exemplar that it is today have shuffled off this mortal coil in recent years. And, sadly, we lost another one this week with the passing of Forest River CEO Pete Liegl. This comes just a few months after Liegl handed off some of his day-to-day responsibilities as part of the RV maker’s new succession plan.

When Warren Buffett acquired Forest River back in 2005, he called Liegl a “remarkable entrepreneur” and noted that “Pete and Berkshire are made for each other”. Liegl was a fascinating man: He built his first RV by hand in a barn and took inspiration as a leader from Saint Peter the Apostle.

Liegl once explained the secret of his success: “The best product at the best price is everything. If you have that … success is going to be forthcoming. There’s nothing more. Then, service it. Take care of it. Be a man of your word. Do what you say you’re going to do.”

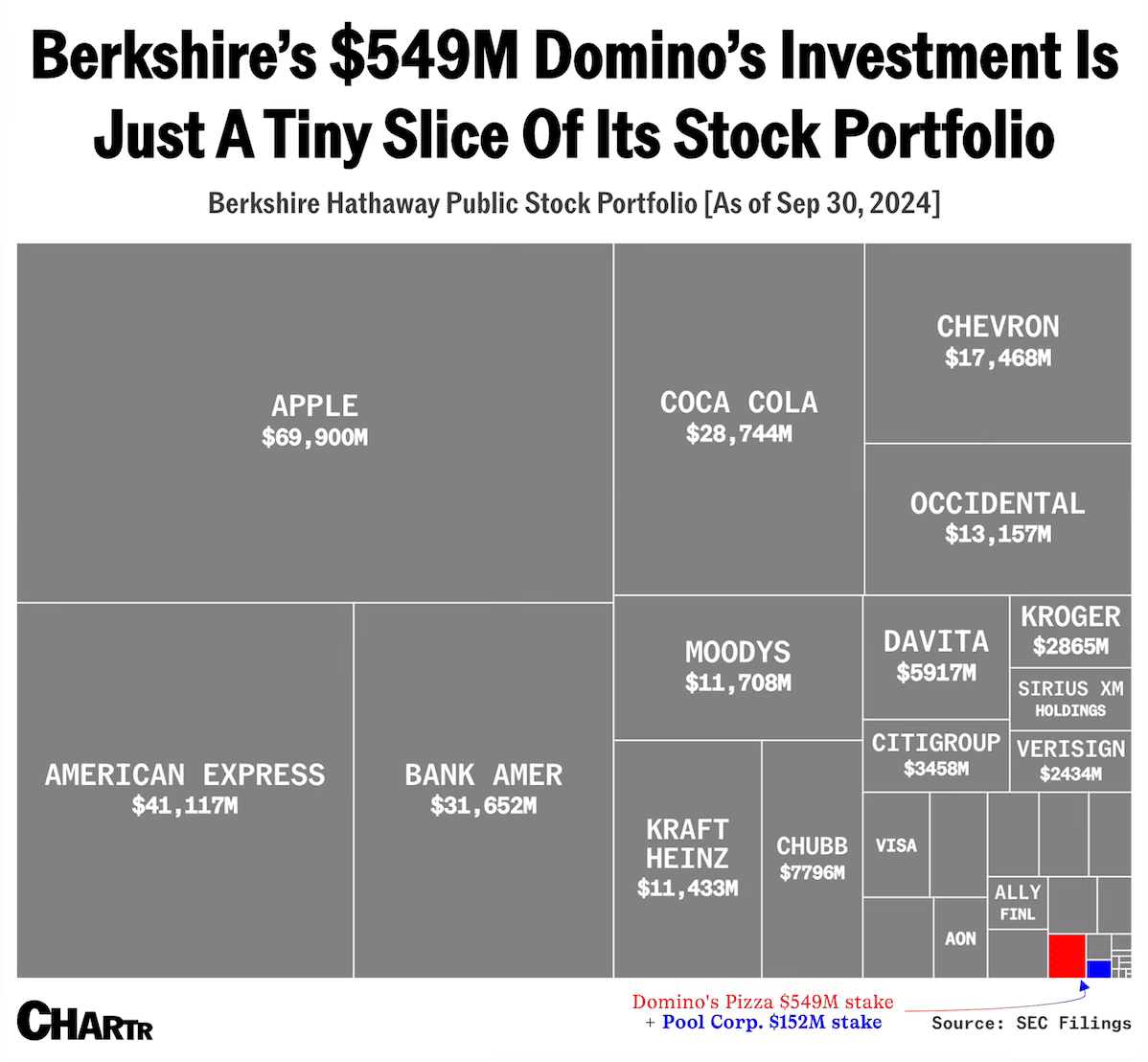

Berkshire didn’t do much buying in Q3 2024. The two new stock positions — Domino’s Pizza and POOLCORP — are both small by Berkshire standards and almost certainly not Buffett’s handiwork.

Jason Zweig tackles Berkshire’s massive $305.5 billion mountain of cash in the latest issue of his newsletter — and asks: “Is it humanly possible to find enough undervalued investments to put a third of a trillion dollars to work?” He comes to the conclusion that a dividend is (eventually) all but inevitable. “Shareholders aren’t likely to complain too much about drowning in cash so long as Buffett remains in charge,” writes Zweig, “but I think his eventual successors will have to initiate a dividend. I doubt they will have much choice.”

I agree that a dividend is a matter of when, not if, for Berkshire. But I go back and forth on whether it happens on Buffett’s watch or not. He has made it this far without a dividend and surely would love to keep that streak intact as long as possible. But, since this would be such a dramatic change to Berkshire’s long-standing policy, I wonder if he would prefer to do it himself — and thereby spare Greg Abel the headache of breaking with tradition (and Buffett) by instituting a dividend in the early years of his tenure.

Whenever Berkshire pulls the trigger on a dividend, I imagine that it will look something like Costco’s. A very modest yield with larger special dividends handed out as appropriate. Berkshire director Susan Decker (who also serves on Costco’s board) name-dropped this approach back in May. “Once you start a dividend,” she said, “it can be pulled — but the goal is never to stop. In the hierarchy of choices, a special dividend is something in between. Something that, on the Costco board, we’ve employed really successfully.”

At the time, Decker waved off any talk of a dividend because share repurchases were obviously Buffett’s preferred method of returning cash to shareholders. But, with buybacks on the back burner of late, the drumbeat for dividends will likely only grow louder. Interesting times.

More good news out of BNSF Railway. The Berkshire-owned railroad achieved record agricultural volumes in October — with a 7% increase over 2023. Velocity jumped 7%, too. A result made all the more satisfying after the Surface Transportation Board publicly expressed “grave concerns” over BNSF’s ability to handle this fall’s harvest. (Weather-related troubles slowed agricultural deliveries last year.) In its victory lap, BNSF noted that it handles more agricultural product shipments than any other U.S. railroad.

BNSF also seems to have coped well with record intermodal traffic. The railroad’s focus on improving dwell time over the summer paid off, says analyst Rick Paterson of Loop Capital Markets, when traffic surged on the West Coast in October. “Time will tell, but this looks to me like a structural and sustainable improvement of about 15%.”

CMO Tom Williams talked about the Quantum intermodal service — meant to win back business from the trucking industry with better on-time performance — at the RailTrends conference last week. “We continue to slowly adopt new customers,” he said. “Nobody who’s come in has walked away from that service. And we see this as a big growth opportunity for us as we go into 2025.”

Earlier this week, BNSF took a big step towards fully double-tracking its 2,200-mile-long Southern Transcon route. “This is our busiest corridor, stretching from Southern California to Chicago — and a key route for intermodal trains,” the railroad said on LinkedIn. “Big picture, we can now daily run multiple priority intermodal trains in and out of Southern California between key markets.” Now, only two short stretches of single track — totaling about 4.5 miles in Missouri and Oklahoma — remain on the Southern Transcon.

“Our commitment to growth through investment over the past several decades is one way BNSF is making intermodal service more ‘truck-like’,” said vice president Jon Gabriel. “And, just like a highway, we can run traffic both directions simultaneously with passing lanes when needed.”

🤑 Dividends: This week, Berkshire collected quarterly dividends of $30.9 million from Citigroup, $30.4 million from Sirius XM, and $5.5 million from Capital One.

Back in October, Jazwares senior vice president of global licensing Sam Ferguson spoke at Brand Licensing Europe about the company’s remarkable success. “Squishmallows is definitely — by far — the biggest plush brand in the world. Also, just as a brand, we’re sitting in the top two or three across all toys. It’s been a phenomenal rise to fame in terms of Squishmallows.”

Jazwares has a rare talent for creating products that appeal to all ages. “Tapping into these brands is multigenerational,” said Ferguson. “That’s something that Jazwares does very, very well — in terms of having a product or an action figure that can not only service the kids, but is of such a good quality that the [adult] collector wants it as well.” Thus, future-proofing the company because it’s not just selling to kids — with whom fads come and go as the wind blows — but also collectors who have great emotional investment in particular brands and IP.

I’ve been thinking a lot about this comment from William Green on a recent podcast. “Guy Spier made this clear to me many, many years ago when I was quizzing him about owning Berkshire Hathaway for so many years,” said Green. “Part of Guy’s reasoning was, ‘I want to have Berkshire in my portfolio because I want Warren and Charlie in my portfolio. I want them in my ecosystem to remind me of how to behave.’ I think there’s a deep truth here that you want to bind yourself to people who operate in a moral, upstanding, righteous way that we aspire to operate in ourselves. And [owning Berkshire] slightly tilts the odds towards us behaving well ourselves.”

Costco’s dividend policy is the right model, and it fits Berkshire: both companies have large amounts of cash income, which they can utilize successfully to the benefit of shareholders—Costco to buy real estate on which to build more warehouses; Berkshire to buy opportunistically its shares or other investments. But Berkshire won’t pay a cash dividend until after Warren dies. He does not need a taxable dividend on shares he was designated to society. A cash dividend before he dies would result in a substantial tax diverted from his desired end purpose. What happens after he has gone would best be modeled after Costco. I’m sure he has given considerable thought to this. I suppose he might announce such a plan before he leaves, but he has,yet, no departure schedule.

For those of us who enjoy a cost basis within a rounding error, a dividend of Costco’s is immaterial, but I am quite experienced at picking my own ‘pay’ date. So, I’m largely an agnostic, which means I’m an atheist, thank god. I like the theology!

Berkshire won't pay a dividend. This is why: https://rockandturner.substack.com/p/how-dividends-destroy-shareholder-value