That Time Jim Cramer Got Called Out in "The Intelligent Investor"

No one wants to end up as a cautionary tale in the bible of value investing

[This started out as a light-hearted laugh at how Jim Cramer ended up in The Intelligent Investor, but may have turned out harsher than intended. I typically adhere to Warren Buffett’s “praise by name, criticize by category” principle, so please read this in the chiding-but-not-attacking spirit in which it was written.]

Happy Thursday and welcome to our new subscribers!

The Intelligent Investor, written by the great Benjamin Graham in 1949 and revised several times over the course of his life, is basically the value investing bible.

Warren Buffett called it “by far the best book on investing ever written” and offered his highest praise for two chapters in particular.

“Chapters 8 and 20 have been the bedrock of my investing activities for more than sixty years,” he said. “I suggest that all investors read those chapters and re-read them every time the market has been especially strong or weak.”

Whereas Graham’s earlier treatise, Security Analysis, dove into the nitty-gritty of how to identify and analyze specific instances of undervaluation, The Intelligent Investor addressed the all-important mental and emotional side of the money game.

Graham taught readers to view stocks as tiny pieces of actual businesses (and not just ticker symbols to be traded with gay abandon) and how a rational, grounded mindset can prevent investors from falling prey to Mr. Market’s wild antics.

The Intelligent Investor remains a timeless classic and deserves a prominent place on every investor’s bookshelf.

So just imagine the immense shame of getting called out in those hallowed pages…

Enter Jim Cramer.

Cramer, the colorful (and frenetic) CNBC personality and host of Mad Money, has earned a dubious reputation for himself as the kiss of death.

Over the years, viewers couldn’t help but notice that he possessed an unnerving tendency to promote a stock right before it plummeted in value — or, conversely, turn bearish just in time for a surprising turnaround.

Cramer infamously ruffled more than a few feathers when he made unclear (at best) comments about Bear Stearns — seemingly recommending that investors not sell their stock in the bank — shortly before its collapse in 2008.

It ended up narrowly avoiding bankruptcy and was sold to J.P. Morgan Chase for the stunningly-low price of $2 a share. Anyone who listened to Cramer and kept faith in Bear Stearns probably lost their shirt.

That’s just one of the lowlights that made Cramer something of a punchline among the FinTwit crowd.

His predilection for the incorrect even led Tuttle Capital to create the Inverse Cramer ETF last week, which will allow disgruntled investors to bet against Cramer’s public recommendations.

(On a similar note, if Kingswell ever expands into the merch game, the first product will be a t-shirt or a mug that says “Fade Cramer”.)

But of all Cramer’s many missteps, only one earned him a place as a cautionary tale in the latest edition of The Intelligent Investor.

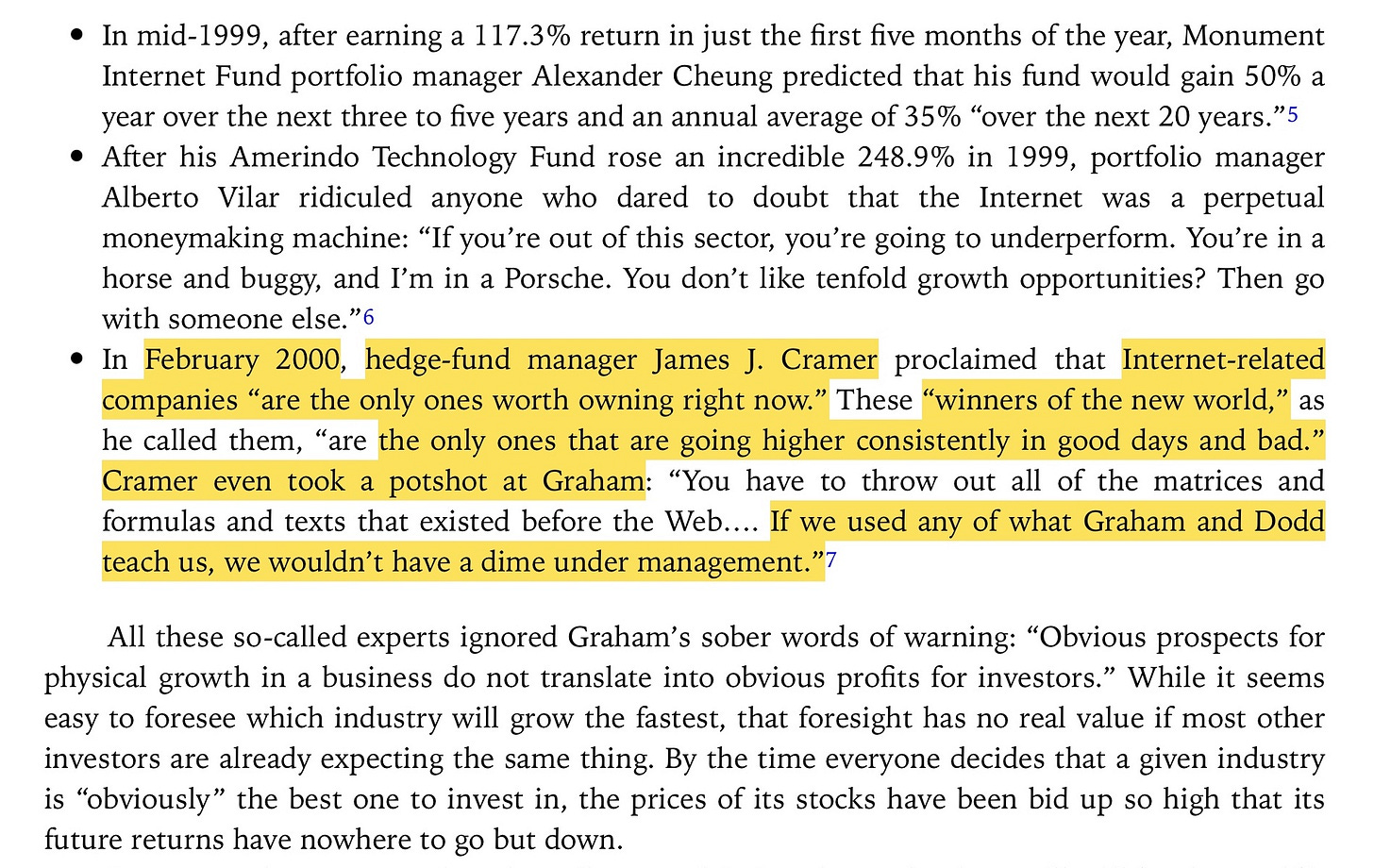

Jason Zweig, the pre-eminent financial journalist of our time, updated the classic text in 2003 and added select commentaries to show how Graham’s timeless wisdom still applied to the then-current day — with investors still reeling from the wreckage of the dot-com bubble and tech crash.

One unlucky example starred our friend, Cramer.

Cramer’s wayward comments came at a presentation he gave on February 29, 2000, at the Internet and Electronic Commerce Conference and Exposition (transcribed by TheStreet) modestly titled “The Winners of the New World”.

And, appropriately enough for Leap Day, it was the moment that Cramer’s reputation leapt off a cliff.

His designated “winners” that day included such leading lights as 724 Solutions, Ariba, Digital Island, Exodus, InfoSpace.com, Inktomi, Mercury Interactive, Sonera, VeriSign, and Veritas Software. A rogue’s gallery of over-hyped, soon-to-be-bust tech startups if I’ve ever seen one.

(To be fair, VeriSign is still around… though it trades at a lower price today than it did at the time of Cramer’s recommendation more than twenty years ago — and spent most of 2001-2005 down 95% from its bubble high. Not exactly a success story.)

“Most of these companies don’t even have earnings per share,” Cramer told the crowd, “so we won’t have to be constrained by that methodology for quarters to come.”

When I first read that quote, I actually had to go back and make sure that this wasn’t a fake story published on some satire website.

But, no, bragging that your stock recommendations aren’t “constrained” by earnings per share — because they had no earnings — was too crazy for satire.

It was real.

“We don’t use price-to-earnings multiples anymore at Cramer Berkowitz,” he continued. “If we talk about price-to-book, we have already gone astray. If we use any of what Graham and Dodd teach us, we wouldn’t have a dime under management.”

Then, to ratchet the madness up another notch, Cramer put in a good word for that dot-com bubble favorite, Cisco. He called it “the quintessential New Economy stock” and said, “It has a currency that is better than U.S. dollars: It has Cisco stock.”

And we all remember what happened with Cisco…

At times, Cramer seemed to be speaking almost tongue-in-cheek about how pre-profit internet stocks had completely displaced the heroes of the old economy. But, at the end, he disclosed that his hedge fund, Cramer Berkowitz, owned all of the stocks that he recommended that morning.

This was no brilliant piece of satire, but a sad artifact of a crazy time when people in high places (like Jim Cramer) really believed that nailing a .com onto the end of a company’s name would send it to the moon.

Well, thankfully for Cramer, Jason Zweig is a gentleman.

And saved his true evisceration of Cramer’s comments for a footnote that few likely ever read.

If anything, Zweig was too kind.

Imagine the investors out there who believed Cramer’s advice and put their money into his “winners of the new world” picks.

A 94% loss of capital is a life-destroying result.

Cramer more than earned his ignominious mention in The Intelligent Investor.

And, since Cisco came up, I’m reminded of a story that Richard Pzena (of Pzena Investment Management) once told about his experiences during the dot-com bubble and its grisly aftermath.

During those heady days in the late nineties, it was increasingly difficult to remain true to a value-based investing approach — especially when the rest of the market had seemingly lost its mind in a speculative frenzy.

I sat down across the table from somebody who said to me, “My grandmother’s a better investor than you. This is very easy. She gets it, you don’t. All you have to do is buy Cisco. How come you won’t buy Cisco? How does my grandmother know this, and not you?”

That was the kind of conversations we were having, so it was not fun.

My response to the grandmother comment was, “Can I just walk you through some arithmetic, because Cisco has a $500 billion market cap. Let’s say you’re going to buy the whole company. You’re rich and you’re going to write a check for the $500 billion, and you want to make a 15% return on your investment. That’s $75 billion. They have to make $75 billion every year. They’re making $1 billion! I mean, something’s wrong, isn’t it?”

And they would just look back and say, “You just don’t get it.”

And I would agree, “Obviously, I don’t get it.

Cisco, of course, lost 85% of its value between March 2000 and March 2001.

A lot of money went up in smoke because people desperately wanted to believe that valuations didn’t matter anymore.

At times like that, we needed trusted people to stand up and say that the emperor had no clothes.

Like Warren Buffett famously did at Sun Valley in 1999.

But the Jim Cramers of the world instead chose to egg on the manic crowd. Reinforcing our base desires for get-rich-quick thinking and immediate gratification.

In many ways, Cramer is Mr. Market made flesh.

And anyone who hangs on every word from Mr. Market will suffer far more losses than gains.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this issue of Kingswell, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends (and enemies) so they don’t miss out. It only costs you a few clicks of the mouse, but means the world to me. Thank you!

Disclosure: This is not financial advice. I am not a financial advisor. Do your own research before making any investment decisions.