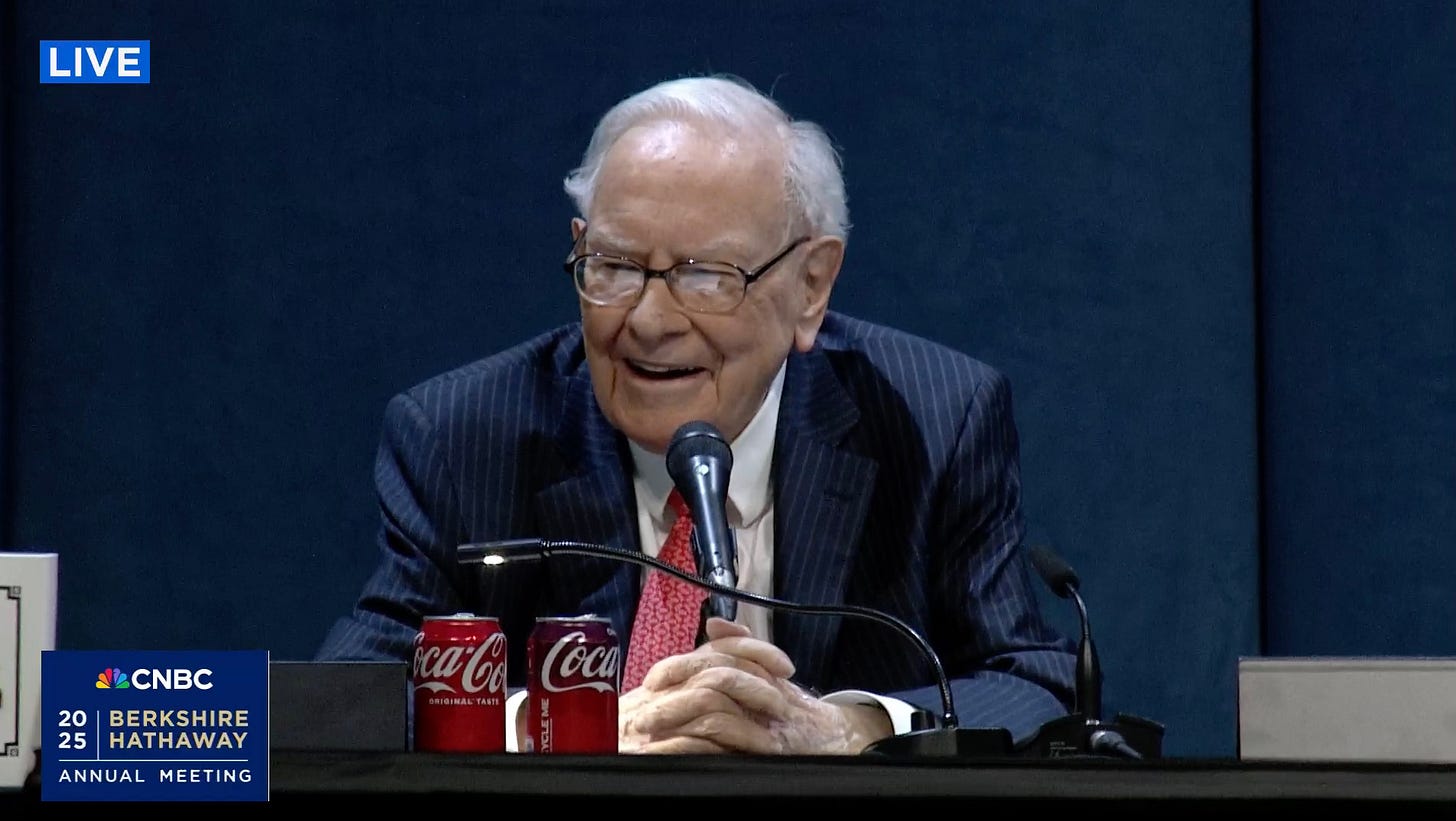

Signing Off After Sixty: Warren Buffett Leaves The Stage (At Year End)

"I have no intention of selling one share of Berkshire Hathaway," said Buffett. "I think the prospects of Berkshire will be better under Greg's management than under mine."

On Saturday morning, Warren Buffett stepped onto the stage at Omaha’s CHI Health Center and was greeted by a sea of devoted shareholders celebrating six decades of his leadership atop Berkshire Hathaway.

A few hours later, he left them speechless by calling time on his storied career and announcing that he intends to pass the CEO reins to vice chairman Greg Abel at the end of this year.

With that, 2026 will officially mark the dawn of a new era for one of the world’s largest (and most admired) companies. And a bittersweet farewell to an exemplar without equal.

In an interview before Buffett’s bombshell, Activision co-founder Bobby Kotick (and friend of the late Charlie Munger) perfectly captured the Berkshire AGM’s deeper significance to so many. “This event is a reminder of how important capitalism is as the foundation of democracy,” he said. “It’s almost like a religious experience from that perspective.” His words reflect the reverence many attendees feel for Berkshire — not just as a financial titan, but as a philosophy rooted in patience, prudence, and long-term thinking.

In light of the big news, today’s article will obviously be dominated with discussion of Buffett’s exit and Abel’s ascendance. Some of the other topics that I planned to write about will be put on ice and returned to in the coming weeks.

(But, rest assured, we will cover just about everything from the AGM and 10-Q in due time. I actually think it’s better that way. I absorb information better when it’s spread out and not packed into one marathon post that causes people’s eyes to glaze over.)

Buffett Bows Out

In hindsight, maybe I should have seen it coming.

Right at the start of Saturday’s meeting, Warren Buffett made a special point of praising the leadership (and, implicitly, the transition) of Steve Jobs and Tim Cook. He lauded Jobs for building Apple and his chosen successor for scaling it. “I’m somewhat embarrassed to say that Tim Cook has made Berkshire a lot more money than I’ve ever made [it],” laughed Buffett.

What seemed like a nice nod to Berkshire’s largest stock holding now feels like a model for Buffett’s own succession. Of a legendary steward handing his life’s work over to a handpicked successor tasked with taking it to new heights.

Details on Buffett’s retirement remain scant. He plans to hang around to help with big decisions — “I could be helpful, I believe, in certain respects if we ran into periods of great opportunity” — but promises that all operational and capital allocation decisions will be Greg Abel’s alone.

According to CNBC’s Becky Quick, Buffett told her off-camera that the board would decide whether or not he stays on as chairman. (The answer better be yes.) If he does, there’s no reason why his annual letters — which he signs as chairman — could not continue. Along with one from Greg, too. (What can I say? I’m greedy.)

But one thing is clear: Buffett is still all-in on Berkshire.

“I have no intention of selling one share of Berkshire Hathaway,” said Buffett. “That’s an economic decision because I think the prospects of Berkshire will be better under Greg’s management than under mine.”

Departing board member Ron Olson — caught off-guard by Buffett’s announcement like everyone else — offered a compelling vision for the immediate future. “I am very anxious to see Warren become the Charlie Munger for Greg Abel,” he told CNBC.

If that’s what Berkshire’s new normal looks like, sign me up.

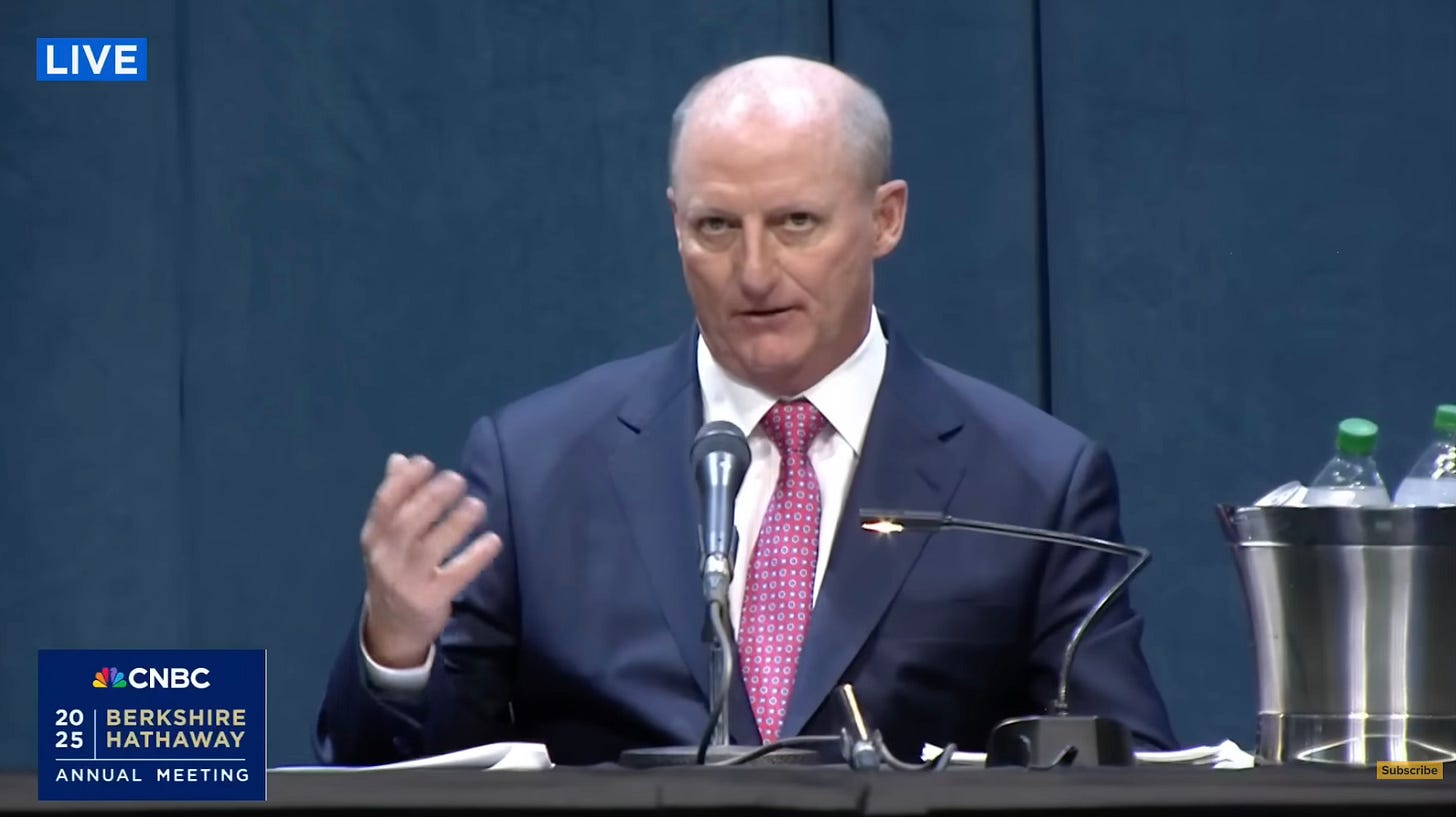

Greg Abel Is Ready

They say that you never want to replace a legend.

But Greg Abel has been preparing for this moment for years. Since becoming vice chairman of non-insurance operations in 2018, he has taken on more and more responsibility for Berkshire’s sprawling portfolio of subsidiaries and managers.

“In the last year, the board and Greg and Warren have moved from preparing for succession to actually practicing it,” said lead director Sue Decker on Friday. “Greg has gotten much more involved with capital allocation decisions.”

“So, increasingly, he is taking on that leadership. We don’t really even see him as a CEO-in-waiting. He is taking on that leadership capacity right now.”

Speaking of capital allocation, Abel acknowledged that Warren and Charlie had set a very high bar in this respect over the past six decades. But he pledged to preserve Berkshire’s unique culture — and let it guide all decisions under his watch.

“We’ve got a significant set of cash right now,” said Abel, “but it’s an enormous asset to have that. That will continue to be a philosophy … and it allows us to weather the difficult times and not be dependent on anybody.”

“We will remain Berkshire. We will never be dependent on a bank or some other party for Berkshire to be successful.”

Abel added that he plans to hold tight to “an identical [capital allocation] philosophy” as his predecessor. In other words, investing in Berkshire’s owned operating businesses (as needed) and acquiring companies in whole or in part. And, in terms of stock purchases, he hammered home the point that Berkshire will always invest with a long-term mindset and view its shares as pieces of actual businesses.

This whole answer was music to my ears.

As Abel mentioned here, Berkshire is sitting on a lot of cash right now. $328 billion to be exact. One of the funnier moments from the meeting came when Buffett was asked if he was hoarding the money to give Abel a clean slate and plenty of dry powder to start off with. “I wouldn’t do anything nearly so noble as to withhold investing myself just so Greg could look good later on,” he laughed. One of CEO Abel’s early challenges will be resisting the urge to spend this cash just for the sake of spending it — a discipline that Buffett has long mastered.

Check Your Emotions At The Door

Amid global trade tensions, everyone wanted Warren Buffett’s take on tariffs and the recent market turmoil. Buffett, predictably, is no fan of tariffs — but he poured cold water on the idea that this past month of volatility was anything major.

“What has happened in the last 30, 45, 100 days — whatever this period has been — it’s really nothing,” said Buffett. “There have been three times, since we acquired Berkshire, that Berkshire has gone down 50% in a very short period of time.”

“[The last month] is not a huge move … This has not been a dramatic bear market or anything of the sort.”

Buffett urged investors stay grounded. “If it makes a difference to you whether your stocks are down 15% or not, you need to get a somewhat different investment philosophy. The world is not going to adapt to you. You’re going to have to adapt to the world.”

The S&P 500 is only down ~3% so far this year — and the benchmark index has already erased all of its post-Liberation Day losses. If people are panicking over this, they are not ready for what might lie ahead. “You’ll see a period,” he said, “certainly in the next twenty years, that will be a ‘hair curler’ compared to anything you’ve seen before.”

“That’s just part of the stock market. That’s what makes it a good place to focus your efforts if you have the proper temperament for it — and a terrible place to get involved if you get frightened by markets that decline and get excited when stock markets go up.”

“People have emotions,” said Buffett, “but you’ve got to check them at the door when you invest.”

Afterwards, Becky Quick admitted that she had to throw out lots of shareholder questions (about foreign countries dumping Treasuries, the dollar, etc.) that were submitted in April — but already seemed outdated. “They were relevant three weeks ago,” said co-host Michael Santoli. “And now they’re not,” laughed Becky.

Looking back on the AGM as a whole, this is the kind of moment that I will miss most when Buffett rides off into retirement. His quasi-contrarian way of cutting through fleeting noise to deliver a timeless lesson on discipline, patience, and perspective.

What’s fascinating is that Buffett’s transition isn’t just a succession story — it might be the final chapter of the American industrial conglomerate model. Berkshire is a relic in the best sense: decentralized, cash-heavy, and uninterested in short-term signaling. But post-Buffett, can that model survive the gravitational pull of financial engineering, activist pressure, and indexation flows? Abel may have the temperament, but the ecosystem has changed. Berkshire’s greatest challenge might be staying weird in a world that punishes patience.

One for your weekend cuppa

https://caffeinatedcaptial.substack.com/p/sunday-big-think-capitalisms-last