No Joke... Digging Through Old Annual Reports Can Be Fun

Happy Friday!

Unearthing Treasure in Old Annual Reports

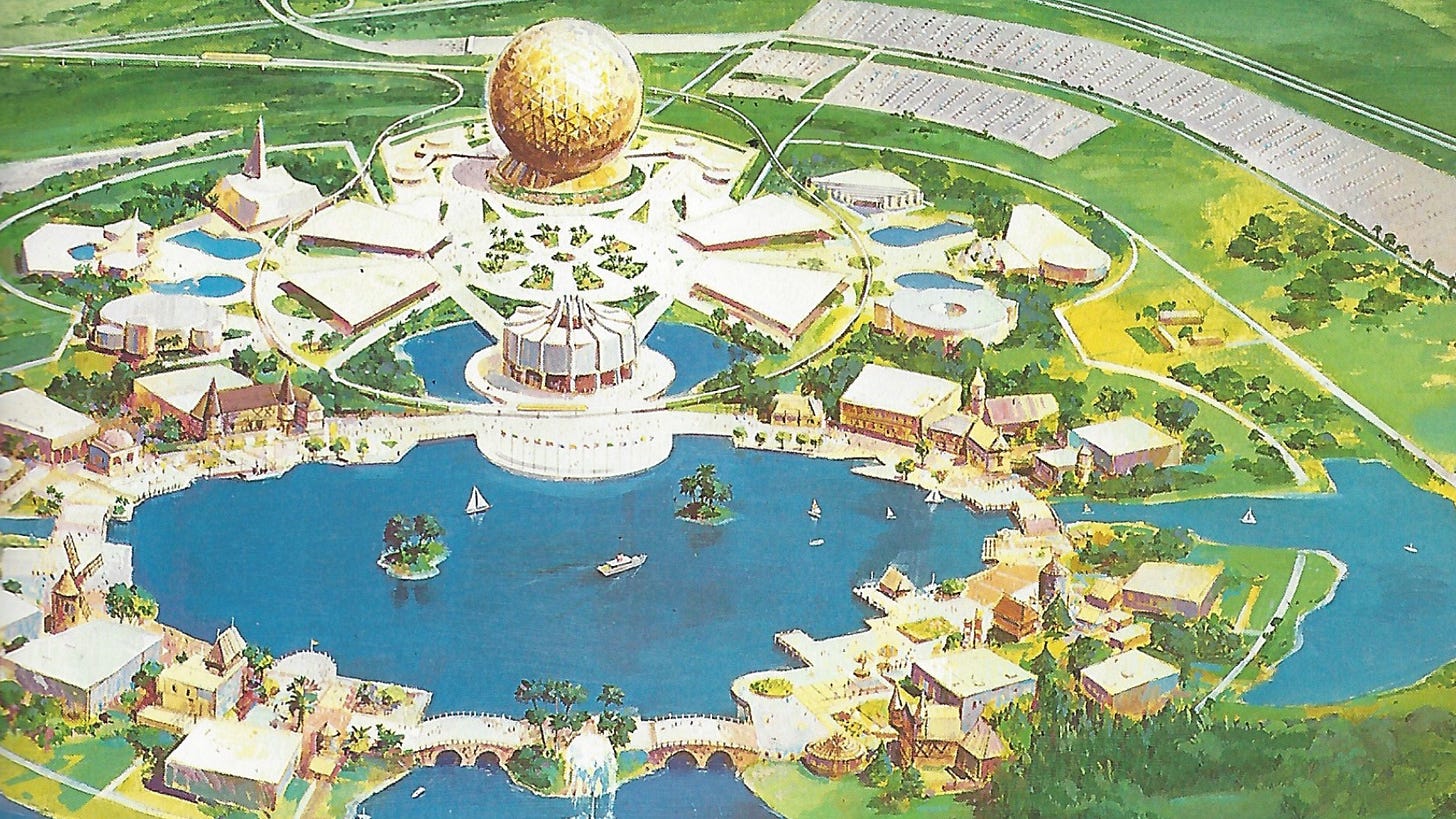

Earlier this week, I was digging through some old Disney annual reports from the 1970s and stumbled on amazing concept art for what would eventually become EPCOT.

For those who don’t know, EPCOT was a bit of a problem child for Disney in the ‘70s. It was originally announced as an actual “city of the future” in 1966, but that concept quickly fell by the wayside after Walt Disney’s untimely death. In the ensuing decade, the Imagineers at WED Enterprises struggled to tweak and transition EPCOT into a more conventional theme park.

This concept art (created just as the final idea for EPCOT began to take shape) provides an interesting peek behind the curtain at how one of the world’s biggest companies prepared for a major new addition.

Newspaper Archives Can Pay Off, Too

I also came across an old Wall Street Journal article written by Dr. Jeremy Siegel in March 2000. Or, as investors remember it, the height of the dot-com bubble.

The Wharton professor took to the pages of the WSJ to, once again, express skepticism in overvalued companies like Cisco and point out the dangers of investing in companies with unusually high P/Es.

Siegel’s cold shower of pragmatism won him few friends during those heady dot-com days. Turns out, though, he was right.

In this WSJ article, Siegel highlights two historical examples of supposedly sterling investments that fell prey to over-valuation:

In the late 1960s, Polaroid was at the top of its game, dominating the photographic field and enjoying one marketing success after another. Investors bid the stock up to an unheard-of 95x earnings. Never before had a large-cap stock been priced so high. But Polaroid’s earnings growth had exceeded 40% a year over the previous fourteen years and the future seemed even brighter.

IBM became the most valued stock in the world in 1967 and held onto that position for more than six years. The dominant computer manufacturer enjoyed enviable margins and virtually no competition. Its stock value reached 50x earnings, a striking multiple for the world’s largest company. But why not? IBM had regularly cranked out 20% annual increases in earnings from the early 1950s and the future obviously belonged to technology.

Yet investors who purchased these and many other stocks when the future looked brightest had much to regret. Polaroid faltered badly and its stock gave investors negative total returns over the next thirty years. And, despite IBM’s comeback under CEO Lou Gerstner, the company’s return has been less than half that of the S&P 500 index over the past generation.

Siegel lamented that far too many investors were “unfazed by history” and too easily seduced by the siren song of unlimited growth.

Interestingly, though, the good doctor was not bearish on the importance of technology. Just the insane valuations.

The excitement generated by the technology and communications revolution is fully justified, and there is no question that the firms leading the way are superior enterprises. But this doesn’t automatically translate into increased shareholder values.

There is a limit to the value of any asset, however promising. Despite our buoyant view of the future, this is no time for investors to discard the lessons of the past.

That last paragraph is pretty much Kingswell’s mission statement.

Disclosure: This is not financial advice. I am not a financial advisor. Do your own research before making any investment decisions.